At its board meeting two weeks ago, the Reserve Bank of Australia cut the “cash rate”, the rate it charges to lend to the banks, from 2.5% to 2.25%. They took this step because the evidence was that economic conditions were deteriorating so rapidly that even the risk of a house price boom was preferable to inactivity on the interest rate front and the resulting intensifying economic slowdown.

We have warned for some time that the slump in mining investment would reduce GDP growth, but that natural slowdown was worsened by a collapse in commodity prices and government warnings about tax increase and welfare cuts and the deficit problem which spooked the public into closing its wallets and purses. Although the RBA’s delay in cutting rates was understandable — they feared igniting a runaway boom in house prices, and all the evidence suggest that the best way to avoid a bust is to temper the previous boom — it has also meant that the overall economic recovery has been delayed. We now expect 2015 to be a year of near recession in Australia, and repeat our forecast that the cash rate will be cut further, and that the stock market will tend to rise. The good news is that this change of heart by the RBA means that Australia will avoid a deep recession.

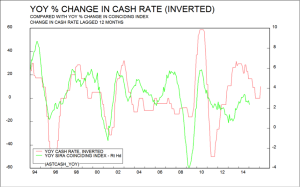

But the rate cut won’t re-energise the economy immediately. Typically the economy lags changes in interest rates in either direction. The chart left shows the year-on-year percentage change in the cash rate, inverted (because the economy recovers when the cash rate falls, and falls when the cash rate rises), compared with our measure of the economic cycle, our coinciding index. In the chart, the change in the cash rate has been plotted with a 12 month lag. On that basis, it would suggest that the economy will start to recover in 2016, but — and this is important — only if there are further cuts in the cash rate. The cash rate could reach 2% or lower, by year end. We shall see.

But the rate cut won’t re-energise the economy immediately. Typically the economy lags changes in interest rates in either direction. The chart left shows the year-on-year percentage change in the cash rate, inverted (because the economy recovers when the cash rate falls, and falls when the cash rate rises), compared with our measure of the economic cycle, our coinciding index. In the chart, the change in the cash rate has been plotted with a 12 month lag. On that basis, it would suggest that the economy will start to recover in 2016, but — and this is important — only if there are further cuts in the cash rate. The cash rate could reach 2% or lower, by year end. We shall see.

Provided we are right in believing that Australia will avoid deep recession, these cash rate cuts will push the stock market higher. Since a falling cash rate will also drive down the Australian dollar, the returns on unhedged international assets (shares or bonds) are likely also to be satisfactory, as indeed they have been over the last couple of years.