In Greece, an old-fashioned socialist political party, Syriza, has been elected to the Greek government, almost winning a majority in its own right. The second largest party is a neo-Nazi party called (in English) ‘Golden Dawn’; the centrist parties have been decimated. In Spain, ‘Podemos’ (‘We can’), another party opposed to austerity and intending to ask for some debt forgiveness, would win an election if it were held now. Syriza is reversing austerity measures originally imposed by the ‘Troika’— the European Central bank (ECB), the European Community (EC) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) — as condition for loans extended to the government in the last Euro crisis, and is renegotiating its debt terms with the Troika.

It’s quite true that Greece brought its initial crisis on itself. The government borrowed heavily and lied about the deficit and its outstanding debt before the first crisis. But then the Troika imposed swingeing austerity on Greece—a one third cut in the minimum wage, cuts in government spending, cuts in government salaries, cuts in pensions, welfare cuts, and of course, tax increases. Similar conditions were imposed on all the crisis countries (Portugal, Spain, Italy, Ireland & Greece.) The net effect of this sharp contraction in government spending was to stop the European recovery in its tracks.

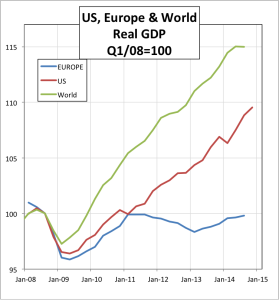

The chart left shows GDP in real terms, i.e., after adjustment for inflation, indexed to 100 in Q1 2008, which is when the GFC began. European real GDP is still below the pre-GFC level, and is rising much more slowly than US real GDP (red) or world GDP (green). It can be observed that initially, Europe followed the US up out of the deep recession lows, but then in 2011, as government spending cuts and tax increases took effect, it turned down again. At the same time, the ECB was slow to respond to the crisis, even at one point bizarrely raising interest rates. In the US, on the other hand, the Federal budget deficit was allowed to balloon during and immediately after the GFC (despite debt exceeding 100% of GDP), and was only cut once economic recovery was secure. The discount rate was slashed to zero, and when growth remained sluggish, a policy of quantitative easing (QE), was initiated to give even more impetus. The different results from the different policies in the US and Europe are very clear.

The chart left shows GDP in real terms, i.e., after adjustment for inflation, indexed to 100 in Q1 2008, which is when the GFC began. European real GDP is still below the pre-GFC level, and is rising much more slowly than US real GDP (red) or world GDP (green). It can be observed that initially, Europe followed the US up out of the deep recession lows, but then in 2011, as government spending cuts and tax increases took effect, it turned down again. At the same time, the ECB was slow to respond to the crisis, even at one point bizarrely raising interest rates. In the US, on the other hand, the Federal budget deficit was allowed to balloon during and immediately after the GFC (despite debt exceeding 100% of GDP), and was only cut once economic recovery was secure. The discount rate was slashed to zero, and when growth remained sluggish, a policy of quantitative easing (QE), was initiated to give even more impetus. The different results from the different policies in the US and Europe are very clear.

Meanwhile, in Greece, Spain, etc., the second (“double dip”) economic downturn from 2011 onwards was even worse than it was for Europe as a whole. In Greece and Spain, unemployment has risen from 7% to 27%; youth unemployment is twice that. Real GDP continued to slide, industrial production stagnated, and as a result, despite tax increases and spending cuts, the ratio of debt to GDP in Greece has risen instead of falling, from 140% of GDP after the last debt restructure in 2012 to 180% now. The decline in real GDP and industrial production and the rise in unemployment was as bad as in the US and Europe in the great depression in the 1930s.

Clearly a continuation of the current policies isn’t going to work. The election in Greece and the polls in Spain suggest that the willingness of ordinary people to endure further austerity has come to an end. The problem for Germany and the other creditor nations in Europe is that if concessions are made to Greece, other struggling economies will also want the same, and that will end up very expensive. But equally, if Greece’s debts aren’t restructured, Greece may default, and be forced to leave the Euro common currency. The new Greek currency (the drachma, again?) will devalue abruptly, and the Greek economy would recover strongly. Under such a scenario, Spain and Italy would both be tempted to follow Greece out of the Euro, which would leave it as a purely northern Europe currency union, with adverse effects on German growth as the Euro soared.

Compromise is still possible. For example, the outstanding Greek debt, instead of having its face value cut, could be refinanced at lower interest rates for longer terms, in return for Greece not dumping all the austerity measures. Both sides are waiting to see who will flinch first, and that could be dangerous, especially since Syriza is dominated by young inexperienced politicians, with enthusiastic supporters with high expectations. Whatever happens, though, the ECB and the European elites have been served notice that different policies to those now in place will have to be instituted or the decades-old dream of a continent-wide currency union is dead.