The US economy has finally started a sustained recovery. After the GFC (Global Financial Crisis), the US federal government and the US Federal Reserve Bank pulled out all the stops to make sure that the financial crisis and the economic downturn didn’t turn into a rerun of the 1930s Great Depression.  The initial “bounce” off the recession lows was reasonably strong but then slowed. The economy stagnated, with growth still positive but not vigorous. Because the “Fed” (The Federal Reserve Bank) couldn’t cut the cash (discount) rate any further since it was already almost zero, the slow recovery prompted them to start a program of quantitative easing (QE). QE involves the Central Bank buying government stock and quality private sector bonds and paying for them with “printed” money. The aim of QE was to provide additional stimulus to the economy, by forcing down long-term interest rates, to encourage investment in housing by individuals, and in plant and equipment by companies.

The initial “bounce” off the recession lows was reasonably strong but then slowed. The economy stagnated, with growth still positive but not vigorous. Because the “Fed” (The Federal Reserve Bank) couldn’t cut the cash (discount) rate any further since it was already almost zero, the slow recovery prompted them to start a program of quantitative easing (QE). QE involves the Central Bank buying government stock and quality private sector bonds and paying for them with “printed” money. The aim of QE was to provide additional stimulus to the economy, by forcing down long-term interest rates, to encourage investment in housing by individuals, and in plant and equipment by companies.

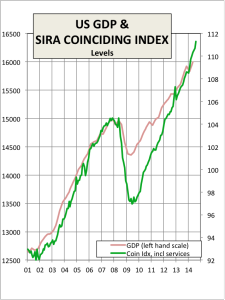

Recently economic indicators suggest that this period of sluggish and erratic growth has come to an end, and that the US economy has finally started a period of self-sustained growth. Unemployment continues to fall, the housing sector is recovering, consumer sentiment is back at pre-recession lows, and even inflation has started to drift up. Real GDP (i.e., the volume of total output, adjusted for price rises) passed its 2007 peak in 2011.

The fly in the ointment is that this economic expansion removes the need for the extremely stimulatory monetary policy which has been followed by the Fed. Already QE is being unwound, and in fact, the last purchases of bonds under this program will take place in October. Meanwhile, the cash (discount) rate, now 0.09%, will have to rise, at some point, back to a more normal level. Historically, a “neutral” cash rate in an economy would be roughly its real long term growth rate plus its targeted inflation rate. Let’s be conservative, and say US long-term growth is 2% per annum and inflation is 2-3% per annum. That would make an appropriate discount rate 4% at least.

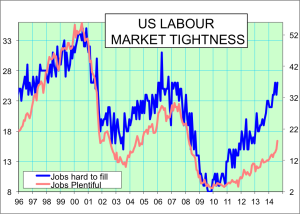

For share markets, the key question is when the Fed will start raising interest rates, and how aggressively it will move. It’s not going to start raising the discount rate just yet. Key to their decision will be signs of tightness in the labour market. So far, although indicators of labour market tightness have risen, they are not yet at high levels. However if the labour market keeps on tightening at the same pace of the last few months, that point may be just 6 or 12 months away. So the Fed could start raising the discount rate in the first half of 2015. Initially, the rise in the cash rate is likely to be slow, because the Fed will be cautious about a move from extreme stimulus to neutral. Unless of course, inflation rises sharply (which we consider unlikely), in which case the increases could be rapid.

For share markets, the key question is when the Fed will start raising interest rates, and how aggressively it will move. It’s not going to start raising the discount rate just yet. Key to their decision will be signs of tightness in the labour market. So far, although indicators of labour market tightness have risen, they are not yet at high levels. However if the labour market keeps on tightening at the same pace of the last few months, that point may be just 6 or 12 months away. So the Fed could start raising the discount rate in the first half of 2015. Initially, the rise in the cash rate is likely to be slow, because the Fed will be cautious about a move from extreme stimulus to neutral. Unless of course, inflation rises sharply (which we consider unlikely), in which case the increases could be rapid.

All the same, the prospect of a rising cash rate may be enough to make the US share market pause, even before rates actually start rising, and despite profits continuing to rise in line with a rising economy. However, a major bear market (i.e., a continuous period of falling prices) is unlikely, because there have been no excesses such as house price speculation and a debt binge as there were before the GFC.