(From G&S’s HMS Pinafore: “This is the consequence, of ill-advised asperity!”)

The GFC (Global Financial Crisis) started in 2008 in collateralised mortgages in the US, but it spread globally. Policy initiatives to restore growth involved deficit spending by governments and drastic interest rate cuts by central banks (e.g., the “Fed” in the US or the RBA in Australia), which led to the beginnings of economic recovery.

But then the new Greek government announced that the previous government had fudged the national debt figures, and that the Greek national debt was much bigger than the official statistics claimed. This started a “run” on Greek debt. As bonds get sold off by investors or sold “short” by speculators, the interest rate (coupon) on new bonds issued has to rise to match the yields on existing (sold off) bonds (yields rise when bond prices fall, and vice versa). If the national debt is a big percentage of GDP, as it was in most developed countries at the time (except Australia) and if the debt is short duration (say 1 or 2 years instead of 10 or 20), this rise in interest rates blows out the government deficit. Say debt equals 100% of GDP and the interest rate on government bonds goes from 2% to 5%, then the deficit, just from higher interest rates alone, jumps from 2% of GDP to 5%. This also means that now the national debt is growing faster than nominal GDP, even if it wasn’t before, which is potentially very serious.

But then the new Greek government announced that the previous government had fudged the national debt figures, and that the Greek national debt was much bigger than the official statistics claimed. This started a “run” on Greek debt. As bonds get sold off by investors or sold “short” by speculators, the interest rate (coupon) on new bonds issued has to rise to match the yields on existing (sold off) bonds (yields rise when bond prices fall, and vice versa). If the national debt is a big percentage of GDP, as it was in most developed countries at the time (except Australia) and if the debt is short duration (say 1 or 2 years instead of 10 or 20), this rise in interest rates blows out the government deficit. Say debt equals 100% of GDP and the interest rate on government bonds goes from 2% to 5%, then the deficit, just from higher interest rates alone, jumps from 2% of GDP to 5%. This also means that now the national debt is growing faster than nominal GDP, even if it wasn’t before, which is potentially very serious.

If, however, it is seen by the central bank as a temporary crisis, it can step in and buy government bonds by “printing” money (in fact, these days, by creating bank reserves electronically), and thus drive up bond prices and cut bond yields. This is called “open market operations”, and this rôle, namely to stabilise government bond markets, was one of the historic reasons central banks were founded. It is an unwise bond speculator who stands in the way of a central bank with unlimited capacity to buy bonds via “printed” money. Such intervention by the central bank in a crisis prevents a self-feeding collapse in bond prices, in the banking system and in the economy.

But the European Central Bank (the “ECB”) didn’t move quickly enough to prevent the first panic from gaining strength and spreading through all the weaker economies of Europe. The surge in bond yields added to already large budget deficits, and since Germany was reluctant to validate what it saw as irresponsible overspending by Greece, Spain, Italy etc., the ECB did not step into the bond markets to conduct “open market operations”, i.e., buy bonds. So bond yields soared. In Greece, 10 year government bond yields rose from 6% to 30%, in Portugal from 5% to 17%! The “creditor” countries in Europe (i.e., Germany) insisted that the “debtor” countries (Greece, Italy, Spain, Portugal and Ireland) slash government spending and raise taxes to restore budget balance before EC (European Community) help would be given.

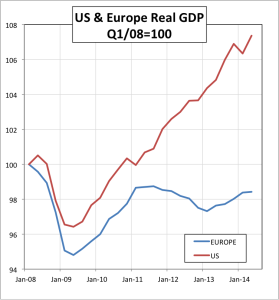

This ill-advised austerity caused the European economy as a whole to go back into recession long before it had even reached the pre-GFC peak. In the chart above, real (i.e., the volume of) GDP for the US (red) and Europe (blue) indexed to Q1 2008, when the GFC began, you can see how European GDP started to recover, then turned down again, before resuming a sluggish upturn. And it is still, 6 years later, below the previous peak reached in Q4 2007.

The US economy on the other hand is more than 10% above the GFC low. Even though the level of government debt in the US was over 100% of GDP, and the deficit over 10% at its worst, the Fed made it clear that it would support the US Treasury Bond market to whatever extent was necessary to prevent meltdown. So long-term bond yields in the US actually fell, rather than soaring as they did in southern Europe. Then, as the US economy grew, tax revenues rose, and government expenditure was reduced, partly through the natural processes (falling unemployment, for example) and partly through expenditure cuts, so the budget deficit fell.

In both Europe and the US since the GFC, deficits have fallen: in Europe, from 6% to 3% of GDP, in the US from over 10% to a projected 2.8% this year. The difference is that the US has recovered, with all that implies (falling unemployment, rising confidence, less economic misery), while Europe has not.

There are a few morals to this story. But perhaps the most important is that you shouldn’t slash spending and raise taxes during the recession. Wait until recovery is well underway before attempting to restore fiscal balance, and the recovery itself will do part of the job for you. This is a lesson very relevant to Australia.