In the 12 months to June 2014, the median house price in Melbourne rose by 19.6%, and in Sydney by 17%. These are very large numbers. If this were to continue over more than one year, it would be deeply concerning, for two reasons. First, these sorts of growth rates would mean that median house prices would double every 6 or 7 years, which would price everybody except for existing owners out of the market. Second, such a boom would encourage borrowers to take on more credit relative to income and banks to lend more and on more generous terms. The GFC was caused by a runaway US (and UK and Spanish and Irish!) housing boom, which when it ended took down the US and other banking systems, and US and global economies with them. The strongest lesson from the GFC for Central Banks and policy makers is that the best way to prevent the dire consequences of a bursting asset bubble is not to let the bubble develop in the first place.

Last year was unusual though. Over the last 8 years, the growth rate in median prices has been much more moderate. Since 2006, the compound annual rate of growth has been 5.6% in Sydney and 7.4% in Melbourne. Although house prices are lower in the other capital cities, the long term annual rate of growth in these cities has been only marginally lower (3.5-4.5%) than in Australia’s two largest conurbations. It’s worth noting that even at 5% per year, house prices would still double every 15 years.

Ultimately, house price growth is dependent on wage/income growth, because mortgage payments or rents have to be affordable. If house prices grow much faster than wages, the portion of income devoted to mortgage repayments or rent will rise unsustainably. As with share prices, movements in interest rates will impart a cycle to house prices. If the mortgage rate halves, then house prices could be theoretically expected to rise, because on unchanged wages/incomes, the monthly payments will be reduced. For example, a halving of the mortgage rate from 10% to 5% for a 25 year repayment mortgage will lower payments by 36%, allowing prices to rise by 50%. For an interest-only mortgage, payments will fall by 50%, allowing prices to rise (theoretically) by 100%.

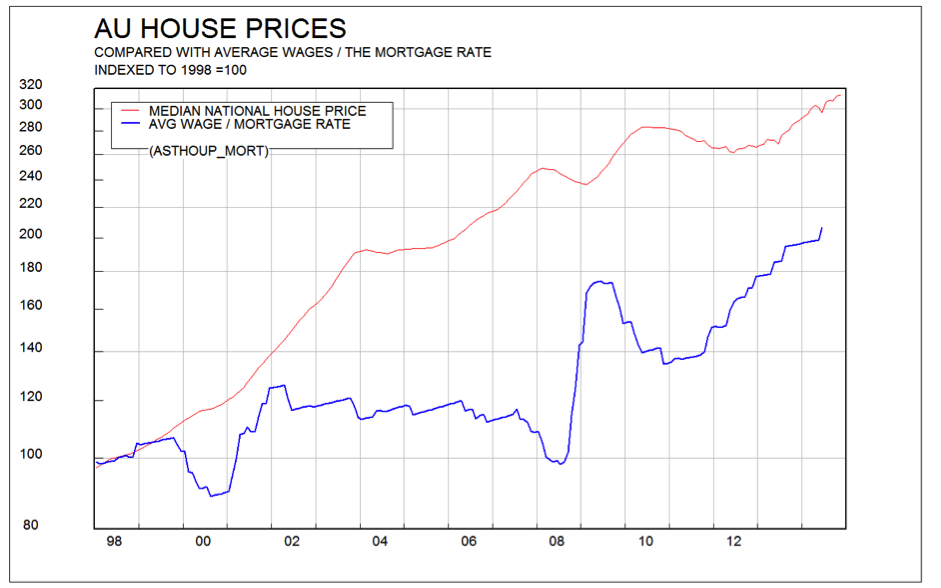

The chart to the left shows the median national house price compared with average wages divided by (discounted by) the average mortgage rate. This metric will rise when wages rise, or interest rates fall, and will fall when interest rates go up. As you can see from the chart, since 1998 a 50% gap has opened up between this “affordability index” and actual house prices.

The chart to the left shows the median national house price compared with average wages divided by (discounted by) the average mortgage rate. This metric will rise when wages rise, or interest rates fall, and will fall when interest rates go up. As you can see from the chart, since 1998 a 50% gap has opened up between this “affordability index” and actual house prices.

Economic growth in Australia is faltering, as the mining boom tails off. The Reserve Bank (RBA) has already cut the cash rate from 4.75% to 2.5%, and this (via falling mortgage rates) has fuelled a 20% rise in median national house prices since mid-2012. Since house prices lag changes in interest rates/affordability, there are certainly more price rises in the pipeline, even if mortgage rates fall no further. Although the RBA would like to cut the cash rate further to help the economy grow, it is reluctant to do so because of the risk of a housing bubble developing. At the same time, wage growth is slowing, to levels not seen for 30 years. Affordability is only going to improve very slowly, absent big rate cuts.

Unless the RBA cuts the cash rate again, it would seem that house price inflation will likely slow over the next couple of years. On the other hand, a fall is unlikely , unless the cash rate is raised substantially, which in our view won’t happen for the next year or more. A period of house price stagnation seems on the cards. The RBA would welcome this outcome.