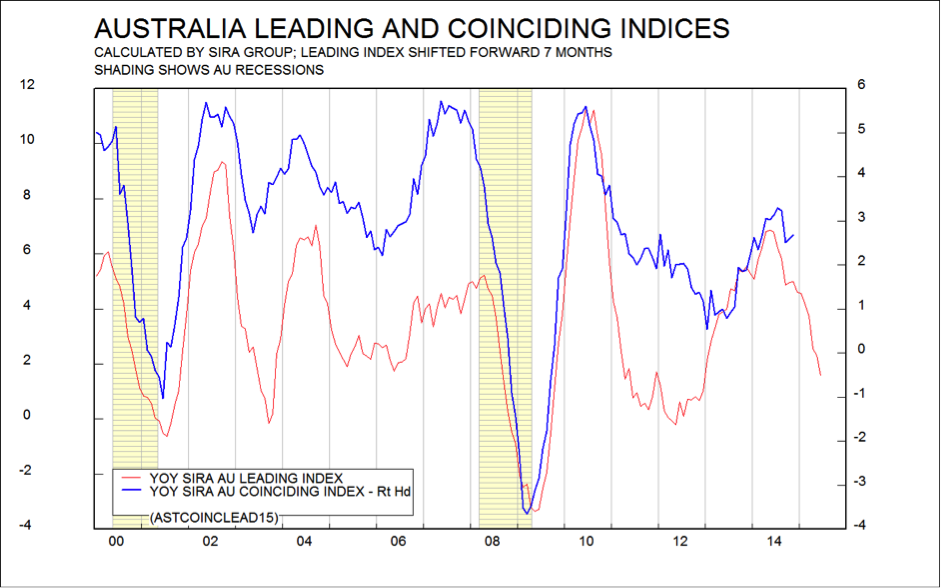

We have been warning for some months now that economic growth in Australia was likely to slow sharply. The latest national accounts data confirm that this slowdown has begun. GDP rose at just 0.4% in Q3 in real (inflation-adjusted) terms, or 1.6% annualised, way below the long term average (since 1960) of 3.5% per annum. Real domestic demand, or GDE, rose just 0.1% in Q3, or 0.4% annualised. Over the last 54 years, real GDE has grown at an average rate of 3.6% per annum. Meanwhile, nominal GDP (i.e., before inflation is removed) actually fell, because the GDP price index was negative, for the first time since the GFC.

Unfortunately, unless the Reserve Bank (RBA) cuts the cash rate aggressively, it is unlikely that these trends will change. Even after rates are cut, it takes a while for the economy to respond, typically 8 months or more. And the RBA is worried that aggressive cuts in the cash rate could lead to a runaway housing boom, so will be very reluctant to cut rates again until they are convinced that the economy is very weak indeed. It doesn’t yet appear that the RBA is convinced that growth is that weak, but we shall see (their next meeting is only in February). Meanwhile, the evidence that the Australian economy is slowing is mounting.

Unfortunately, unless the Reserve Bank (RBA) cuts the cash rate aggressively, it is unlikely that these trends will change. Even after rates are cut, it takes a while for the economy to respond, typically 8 months or more. And the RBA is worried that aggressive cuts in the cash rate could lead to a runaway housing boom, so will be very reluctant to cut rates again until they are convinced that the economy is very weak indeed. It doesn’t yet appear that the RBA is convinced that growth is that weak, but we shall see (their next meeting is only in February). Meanwhile, the evidence that the Australian economy is slowing is mounting.

World economic growth continues to slacken. Europe is stagnant, China is still growing fast by others’ standards but much more slowly than in recent years, and only the US is experiencing a sustained economic upswing. Commodity prices are still declining, because of this. The coal price and the iron ore price have more than halved over the last four years, but the A$ remains stubbornly high. In the past, the impact of falling export prices was softened by a simultaneous fall in the currency. This time, the A$ has fallen against the US$, but not by much, and has actually risen against the currencies of other key trading partners.

What will stop this slowdown?

First, as we said above, the RBA needs to cut the cash rate. Second, the European Central Bank (ECB) needs to introduce much more aggressive stimulus to the European economy, and, at the same time, the European establishment’s ardour for drastically cutting budget deficits needs to be cooled. In China, growth won’t slip below 7%, but nor will it accelerate beyond 8%. The very rapid growth in the past brought immense problems in its wake (corruption, pollution, income inequality, political dissatisfaction). The Chinese leadership is carefully navigating their giant economy into a new era, where growth comes not so much from capital investment but from consumption.

For now, this slowing trend in our economy seems likely to continue.