Many people believe that cutting a government’s fiscal deficit leads to increased confidence and higher growth. The evidence, however, is not terribly convincing.

Many people believe that cutting a government’s fiscal deficit leads to increased confidence and higher growth. The evidence, however, is not terribly convincing.

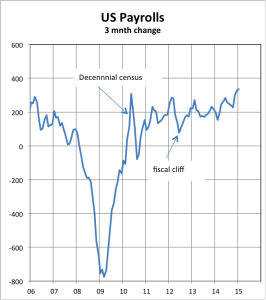

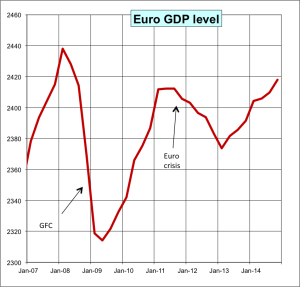

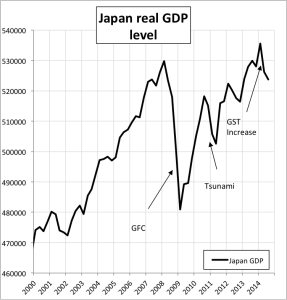

The three charts below show what has happened recently when budget deficits have been cut, either by spending cuts or by tax increases or by both together.

The first chart shows what happened in the US when taxes were raised and spending was cut at the beginning of 2012. Fortunately, monetary policy (run by the Federal Reserve Bank, not the government) remained extremely stimulatory and after a brief pause the economy resumed its recovery. The budget deficit has fallen from 11.4% of GDP at the depths of the crisis to about 2.8% now, mostly because economic growth has upped tax revenues and cut budget outlays.

The second chart shows how European GDP slumped

The second chart shows how European GDP slumped

when the deficit countries within the EU were forced to slash spending and raise taxes to try and balance their budgets. A normal economic recovery started after the GFC only to be aborted by severe fiscal tightening as the Euro crisis took effect after 2011. Unfortunaely, the European Central Bank, the European equivalent of the Federal Reserve Bank, did not provide the strongly stimulatory monetary suport the economy needed to offset the fiscally induced weakness. GDP declined and is still below the pre-GFC peak as a result. And deficits and debt to GDP ratios remain too high, despite Spartan austerity.

In Japan, an increase in the GST from 5% to 8% in April tipped the economy back into recession.  Actually, the same thing happened in 1997 when the GST was increased from 3% to 5%. You’d think they’d learn!

Actually, the same thing happened in 1997 when the GST was increased from 3% to 5%. You’d think they’d learn!

It is undoubtedly true that prudent fiscal policy means that you should aim to balance the budget, or at least, to ensure that current expenditure is covered by tax revenue (there is a good case to be made for funding infrastructure from borrowings). But if you tighten fiscal policy at a time when the economy is already weak, you risk pushing the economy deeper into recession, and because of that, actually worsening the deficit as tax revenue slides. To achieve both balanced budgets and sustained growth, moves back to surplus should be small, slow, and cautious.

The lessons for Australia in its current slowdown are clear.