When I was a rookie investment analyst, more decades ago than I care to acknowledge, the dealer at whose desk I was situated for training taught me about “blood on the streets”. What he meant by this rather gruesome phrase is that when share markets slump precipitously, as European and US markets did overnight, falling by around 4%, this can be a sign that we are close to the lows.

- This sounds perverse, but the reasons for it are simple. If everybody has sold, there is no one left to sell. We’re inclined to buy now, not sell. Why? We sold in January 2008 because it was abundantly clear that the US was going to go into a deep recession. We believe this is not the case now. Even if US growth remains sluggish (around 2%, which we consider very likely), a “double-dip” recession is not on the cards. However, should growth slow to zero, the “Fed” is ready to move back to a policy of “quantitative easing” (QE – what used to be called “open market operations”) where it buys government and other debt to flood the system with liquidity. When it did this a year ago, share markets rallied strongly – the All Ords rose 18%.

- We see clear indications that the current mid-cycle slowdown in the world economy is coming to an end. The normal mid-cycle slowdown was worsened by natural calamities: the earthquake and tsunami in Japan which affected not just industrial production and spending in Japan but also in other Asian economies (except China, which continues to grow solidly) and the US.

- Chinese growth continues to be robust. Yes, there are questions about the stability and safety of their growth path, but there always have been questions, ever since I started following the Chinese economy back in 1992. Since then it’s grown from 4% of the world’s economy to 14%. Most of Australia’s exportsgo to China. China is the world’s largest consumer of raw materials. The Chinese economy will just keep powering ahead.

- The crisis in Europe is exactly what’s needed to force the European politicians to do something. They tried to paper over the gaping cracks in Greece (and failed), they made huffy noises about Portugal and Ireland (which convinced nobody). Now Italy is under the microscope: too big to fail, too big to

bail. So they’re facing crunch time: either they do something substantive, or the euro and probably the whole European Union will fail. It’s up to Germany – they’re rich enough and powerful enough to do something meaningful, something which will probably involve some sort of EU guarantee for Italy and Spain’s debts, perhaps by the issue by the EU of “euro bonds”. Meanwhile, the European Central Bank (ECB) has announced that it will make emergency loans to European banks, and it will also (indirectly) be supporting bond markets in Italy and Spain by accepting Spanish and Italian paper from the banks as security for these loans.

- Unlike the “Lehman Moment” when the markets were shocked by Lehman’s totally unexpected failure over a weekend, and all interbank credit froze, everybody in the markets now is well aware of the risks. This has been a very well publicised crisis. Global banks have better capital ratios, better loan to valuations ratios, better risk measurement, better liquid asset ratios and wiser management than they did at the beginning of the GFC.

- Despite the gloom, a recession in Australia is very unlikely in the near term. The two speed economy still holds sway, and so while parts of Australia are very weak, the totality is held up by booming exports, and anyway the RBA has plenty of room to cut rates if it needs to.

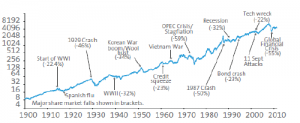

- Our share market is now very cheap. Our “trailing” (i.e., not including forecast profits growth) Price Earnings Ratio (PE) is now the lowest it’s been in over 20 years (excluding the GFC). The market’s dividend yield is back at the 2003 bear market highs, again, the highest in 20 years apart from the GFC. In the longer run, the returns from shares are overwhelmingly positive. Have a look at the chart below, which is from AMP Capital Investors.

This shows the total return (i.e. including dividends) from investing in the Australian stock market, cumulated, over the last 110 years. Their analysis indicates that over this period your money would have grown at 11.8% per annum (or 7.7% after inflation). This includes the Great Depression, the 1970s era of stagflation, the 1987 crash and the GFC. Since 1950, the total return from shares has also been 12% per annum. Since 1980, it’s been 11.5% per annum. Since 1990 the All Ordinaries has returned just 8.8% per annum, because of the market weakness since 2007, but even so, your capital would have risen 6 fold over this period. All these numbers reflect the performance of the index and ignore the added value SIRA group has made by careful stock selection and market timing.

Now is not the time to panic.

As always, we are very happy to talk to you if you have any queries.