To everyone’s surprise and consternation, on Thursday Britain voted to leave the EU. The vote led to some of the biggest one day falls in share and currency markets seen for three decades.

To everyone’s surprise and consternation, on Thursday Britain voted to leave the EU. The vote led to some of the biggest one day falls in share and currency markets seen for three decades.

The first thing that needs to be said is that there will be no immediate changes. The divorce negotiations will take two years, and although European leaders are keen to start immediately, in the UK, both major political parties are in disarray. The Prime Minister David Cameron has resigned with effect from October, and it makes sense that the new P.M., whoever he or she is, will oversee the negotiations. The Labour party shadow cabinet has also resigned, and it seems likely the leader of the Labour Party, Jeremy Corbyn, will be ousted. There may well be a snap general election. So practically, negotiations won’t be able to begin until these issues are settled. Therefore, as regards taxes, import duties, free movement of labour, agricultural subsidies etc., there will be no changes for 2 years starting in October, and even when the changes are implemented there will be a phase-in process. The immediate direct economic impact will be limited.

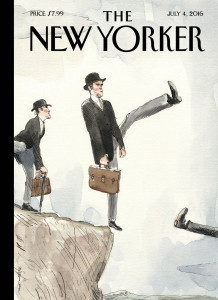

But the longer-term effect on Britain’s economy will be severe. Since the EU will wish to discourage other “exiters”, it will likely set harsh terms for the UK. (In fact, there may not even be a UK to negotiate with, as Scotland overwhelmingly voted to remain in the EU, and will probably have another independence referendum.)

The “Brexiters” in the UK promised before the referendum that there would be much more cash to spend in Britain (since there would be no transfers to the EU), that the UK would have free access to the common market, and that Britain would be able to control population movements from Europe. The trouble is, if Britain wants open access to Europe’s markets it will also have to allow open access and free labour movements to her own markets, so it is unlikely that she will be able to have both. And the EU associates Norway, Lichtenstein, Iceland and Switzerland still contribute to the EU budget—they just get no say in the EU’s councils. At the same time, banks set up in London which get an “EU passport” allowing them to operate across Europe without getting approval from individual EU countries will now lose that right. London is the world’s financial capital, and its financial services are a significant contributor (7%+) to UK GDP. Whichever way you look, the direct negative effect on the UK economy will be significant.

The biggest short-term impact is on certainty and confidence, especially in the UK. And that will worsen the direct economic consequences of leaving the EU, as investment is postponed and multinationals move their operations to an EU country. Ireland could be a big beneficiary, and so perhaps could a newly independent Scotland.

But there are wider implications too. There is a rising trend of anti-establishment politics in developed countries. Brexit, Trump/Sanders, the rise of the far right in France and other European countries, of Corbyn in the UK, and of minor parties in Australia are not idiosyncratic. They reflect the fact that what the establishment stands for (free trade, deregulation, immigration, and tax cuts funded by welfare cuts) has been enormously beneficial for the owners of capital. Over the last 30 years, the rising tide lifted the super yachts but sank many of the dinghies. The rise in income inequality is the single most important economic trend behind the rise of fringe politics everywhere.

In the EU, overall growth since the economic peak in 2008 before the GFC has been a miserable 0.2% per annum. This has exacerbated the contrasts and conflicts in Europe between the poorest people (who feel the brunt of immigration) and their elites, and between poorest and richest countries, for example between Germany and Greece. There will certainly be politicians in other European countries emboldened by Brexit, clamouring for their own referendums, adding to the uncertainty across Europe. After all, the argument against Grexit (Greece leaving the EU) was that it might have a domino effect on other countries. How much more serious is the departure of Britain!

Markets don’t like uncertainty. The more uncertain things are, the greater the discount rate you apply to shares, and the lower share prices fall. Having said that, Australia is much more dependent on Asia than on Europe. China took 36% of total exports in 2013/14, Japan 18%, other Asian countries 28%. Exports to Europe including the UK are just 5.5% of the total. These days the UK buys a princely 1.4% of total exports. (50 years ago, Britain took 23.5% of our exports and Europe another 12.4%.) In addition, the central banks (the Bank of England, the European Central Bank and the Federal Reserve Bank) have all taken steps to expand liquidity and stabilise markets. This is not a “Lehman moment” (the collapse of Lehman in the US in 2008 vastly deepened the GFC)

Although Brexit will have a major impact on the UK’s economy, it will scarcely affect Australia. What happens in China is far more important to us, and we expect the markets to remember that in time. Chinese growth will continue, even if it isn’t at the breakneck pace of 10 years ago. The share market here will recover.